From the BI/CRQ Hyper-Polarization Discussion

On August 22, 2023, I (Heidi Burgess) continued my discussion with Jay Rothman, which I began in June. We blogged about that first discussion, which focused on Jay's and Daniela Cohen's intervention in a deep-rooted, long-lasting school conflict in Yellow Springs, Ohio, in Newsletter 141 (published on July 27, 2023). This second discussion is available in full here.

Recap of our First Discussion

To recap briefly, Yellow Springs's schools were falling apart, yet they had been unable to pass a bond issue to renovate or replace them for six years, even though the community is strongly progressive and historically very pro-school and pro-education. The problem was a clash of values: some people were primarily concerned about the quality of education. Others wanted to prioritize cost, in an effort to keep the already expensive community affordable for its low-income residents. Others wanted to prioritize environmental values, such as not creating lots of waste by tearing down schools and building new ones, or not encouraging development by abandoning some school properties and building new schools in a different location.

Jay, and his partner Daniela Cohen engaged the community in a variety of processes—some one-on-one, some group, even a survey that went out to everyone in the community—to collect information about people's desires, the reasons for those desires, and how they preferred the school district move forward on this issue. (In this second interview Jay explained this basic process was focused on three simple questions: "What, Why and How." What do you want? Why do you want that? How do you think the community should do that? After collecting masses of data, they used ChatGPT to help them pull it all together, and then gave it to the school board which used the condensed data as a basis for a 5-0 consensus proposal for a bond issue which had been completely impossible to develop over the last 6 years.

Our Second Discussion

In this second discussion, I wanted Jay to compare what they did in Yellow Springs to his much earlier (2001-2002) work in Cincinnati, Ohio, relating to police-community relations. Jay reminded me that he had done an interview with our colleague Julian Portilla about his work in Cincinnati in 2003. For those who want a detailed description of that intervention, go to that interview.

In this second discussion, Jay gave us an update on the Yellow Spring situation, we discussed "lessons learned" from that experience, and then we compared that intervention to Jay's work in Cincinnati, There are many lessons in both stories that relate to how and why conflict resolution practitioners can become more effectively involved in the large scale political conflicts of today.

Jay first reported that the agreement reached a couple of months earlier in Yellow Springs is still holding, and that the "vicious cycle" that had lead to a six-year stalemate appears to have been pretty much completely replaced with a "virtuous cycle," where people have finally figured out that they can do much more—to the benefit of everyone—if they work together. While the end of this story won't be known until the November election, right now all indications are that the bond issue will pass, based on a large collaborative process that involved much of the town.

Lessons from Yellow Springs

At the end of that conversation, Heidi asked Jay and Daniela what lessons practitioners and theoreticians could draw from this story that might be applied in other cases. They listed several:

1. Treat community conflicts as systems-level problems. Look at the interpersonal issues, the relational issues, the different identity groups, as well as the structural issues all together to understand how they are affecting each other, and then, what can be done to influence each of those levels and the interactions between levels.

2. Consider whether there are identity issues and value conflicts underlying the apparent interest discrepancies. In difficult conflicts, there very often are value and identity issues, which make compromise and collaboration—even respect and understanding—much more difficult.

3. Use a variety of different processes, each designed to bring in different sets of people. Keep an eye out for who is being left out, and do what you can to include them, possibly by changing the process to meet their needs.

4. Don't let the process become "about you." Let it become about the people involved—let them take the credit. Give people the power to change the trajectory of their own communities. (Though there are some downsides to this approach that we discussed in this second interview.)

5. A last item that Jay also added in this second interview was the value of having a local advisory committee—even if you, yourself, are local (as Jay was in Yellow Springs). Having people outside your immediate team to bounce things off of, to get advice from, and to help publicize the process and get people involved is invaluable.

Comparing Yellow Springs and Cincinnati Interventions

We then turned our attention to Cincinnati, where a federal judge was presented with a number of racial profiling cases, and she asked Jay to be a "special master," (in this case meaning "mediator") who might try to resolve these cases as a class action out of court. At first, the police chief was not at all interested. He said that his department hadn't been racially profiling, and he wanted to prove that in court. So Jay offered another option: to focus less on what happened in the past, and more on what should happen in the future. The Chief of Police agreed, saying "that's what they do anyway, and it might keep them out of court for awhile." The head of the Black United Front was skeptical, but Jay pointed out that there was a federal judge behind this. "f we succeed in coming up with a new agenda for the future, she is going to make sure that it's implemented." Given that, the head of the Black United Front said, “that's good enough. We'll try.” They tried for several months, but the discussions went nowhere. Then, a black youth was shot in the back.as he was running away from the police. The town erupted, and the parties to the racial profiling lawsuits decided there really had to be a better way to move forward.

So, we spent the next year bringing together 3500 people. Basically, through a survey process of asking people, what, why, how? Simple questions. What are your visions for the future of police community relations? Why do you care about them deeply? And how do you want to accomplish them?

We grouped everyone into eight different stakeholder identity groups. Youth, police and their families, city leaders, and so forth, eight different groups. And each group met. After we got their data, we analyzed and organized it, basically through a cluster analysis of what was shared and unique and contrasting across their data. And then we presented it back to them in feedback sessions, four-hour feedback sessions, where each group reached their own internal consensus about the future of police community relations.

Then we brought together the representatives of these groups that were selected by their groups to pull together consensus across the consensus.

Out of that, they came up with five principles for the future of police-community relations in Cincinnati which were turned back to the federal court. They were made into a legal document which was affirmed by the Justice Department, "and then it went forward—in fits and starts—over the next twenty-some years. And it has been fits and starts, but it also has continued."

Jay acknowledged some disappointment with the implementation, particularly because the initial 3500 people lost their voice as things went forward. "I think the issue of trust, the issue of participation, became much smaller [in importance] as the focus on policy changed and best police practices for enhancing police-community relations, funding, and so forth became primary. It should have been both-and [and it wasn't].

Yet one of the results of the process was the creation of a Police Community Partnering Center which was designed to be a place where the police and the community could continue to work together to find ways that community-oriented policing could really work effectively. This center, Jay pointed out, had a very interesting origin:

We were in negotiations in the Judge’s chambers at the end of the process. And the head of the Fraternal Order of Police was saying, “look, we're behind this. We believe in it,” which has gone up and down during the collaborative and afterwards about how much the police leadership was actually committed to this. But at this point, they said they were committed. They said, however, we think we put ourselves into a bad position, because we're going to be held accountable for our changed behavior and the community isn't. So that's not fair. And those representing the community said, you’ve got a good point there. So, what can we do? And so they created this institution called the “Police-Community Partnering Center.”

That center should have been the place where the 10,000 "how ideas" developed by the 3500 original participants actually "got legs," said Jay. At the time of the interview, he wasn't sure it worked out that way. But he noted in a later email that the center has been taken over the the Urban League and still seems to be active 20 years later. (See https://www.facebook.com/cincycppc/ )

Also, he pointed out, the culture of the city changed. Shortly after the agreements were finalized the police chief stepped down.

[Initially,] he had actually been somewhat adversarial to our process, but at this point, he was very much of an advocate of it. And he was replaced by the first African-American chief of police in the history of Cincinnati. That felt symbolically powerful. Since then, there have been several more African-American police chiefs, and now there's an African-American female police chief. Maybe there's no direct line from our process to this dynamic. But there was a change in culture and attitude, so maybe its at least correlated.

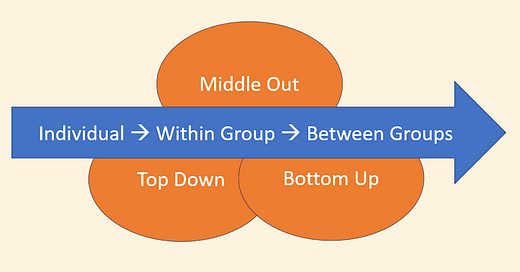

We then went on to discuss the commonalities and differences between Jay's work in Yellow Springs and Cincinnati, focusing in, particularly, on the issue of scale. Both of these processes were designed to transform a conflict that had enveloped a whole community.. One element of success was that they both combined top-down, bottom-up, and "middle out" approaches.

Yellow Springs started from a community organization—The Community Foundation, which approached Jay to find out if he could help Yellow Springs heal their rifts and move forward, somehow, on the school funding impasse. In our discussion, we both said that that was a "top-down" beginning, but I now realize I'd categorize it as a "middle out." Community Foundations are good examples of mid-level institutions. They are not decision making organizations, such as city councils or school boards, but they do hold considerable sway in many communities. The Community Foundation encouraged the participation of the school board (the top level), as well as the grassroots, and Jay took care to create processes that involved all of these levels. He and Daniela held one-on-one conversations with school board members and other local leaders, they had small group discussions, they had community meetings (they called this a "World Cafe") and they carried out a survey that went out to every citizen in the community. So, while the leadership first came from the middle, the top, middle and bottom were all involved in a process which culminated in the identification of four values which needed to be addressed in any consensus solution. Using this data, the school board was then able to develop a proposal for a bond issue which took everyone's values into account, even if it didn't meet any one value 100%. But it included enough of each value to be acceptable to all the board members—who had been elected, primarily to protect one, but not all, of those values. It is hoped that this consensus will be enough to allow for passage of the bond issue at the November election.

The Cincinnati process was similar. That one did, indeed, start at the top, as a federal judge appointed Jay to be a special master. But she quickly relinquished control, and Jay started working with mid-level people (leaders of the main constituency groups) and then moved to a large-scale grassroots process that involved 3500 local citizens from each of eight different interest groups. After collecting data from those 3500 people, 800 of those volunteered to participate in eight different dialogue groups over nine months. Then 80 people representing ten from each of the eight groups reached consensus on five principles for the future of police-community relations and that was made, by the court, into a legal document which was approved at the top by the Justice Department, giving it legal standing and "legs."

So the pattern in each case was the similar: starting at the middle or the top, but then moving down to collect data from the grassroots, and then using a variety of processes to hone this down into four or five basic tenets which were then taken back to the top which took action on the consensus. In Yellow Springs, the School Board has agreed on the terms of a bond issue which will be presented to the voters in the fall (so the ultimate decision, here, is at the bottom) and in Cincinnati, the court and the Justice Department created a legal document requiring Cincinnati to implement a variety of actions to keep the police and the community working together to provide public safety to Cincinnati. So in both cases, who was leading, who was setting the agenda, and who was following kept on shifting.

But, it is important to note that the agenda was no longer being set by "those angry people who were accusing each other of bad faith and antagonism and in that way, stirring it up themselves. [Rather, it was those who were saying] “we can solve problems together. We're in a community together. We care about a better future together.” Jay later reflected back on his work in Jerusalem, where he first developed this value-based, identity-based approach to large scale interventions. There, he said, people used to say to him

so you're working with people who already, to a certain extent, agree with each other. Isn't that a problem”? Don't you need to be working with the extremists who basically want to destroy each other? And I say “No. I'm not probably not going to be able to change their minds or their approaches. But if I can help to support those who already believe that working across their lines is a better thing to do, and give them more skill and will, then extremists are going to get more and more marginalized and those seeking to build alliances are going to grow stronger and wider.”

More Scale-Up Lessons

This seems to us to be a crucial model for peacebuilders in the United States (or other places democracy is threatened). Work to strengthen the middle. Improve their skills, improve their will to work together. Help them build alliances to grow stronger and wider. Only then will they be able to marginalize the extremists (on both sides) who are intentionally (or unintentionally) tearing their communities and nations apart.

When I asked what other suggestions Jay had for scaling up small-scale processes to larger scales, he emphasized the importance of starting small. You start, he said, with the individual.

The individual necessitous being who has needs and values and hopes and fears. And [you] get them involved individually and give them a sense that “my voice matters and my concerns are really important.” ... [You get them to tell you] "this is what I want. This is why I want it. This is how I want it to happen. And then, in that sense itself, [they can] say, “okay, I have made a contribution. My voice is going somewhere.”

Then you get at least some of those individuals to meet and discuss and develop a consensus within their own identity groups, their own sides.

And then the next level is “who am I within this group? And who are the other members of my group?” A lot of people say, “I want to go from the individual to the system.” I say, as an identity framework, I want to go from my voice to the group that I identify most strongly with in this situation. In Cincinnati, they had eight groups they could choose from when they filled out the survey.

And then representatives of those eight groups met in face-to-face meetings over the course of nine months to condense all their ideas into a set of recommendations. Only after they have done that, do you bring the groups together to try to develop a cross-group consensus. By then they have become more comfortable with dialogue, with collaborative processes. They know how it works, and that disagreements can be worked through in that way. So they are in a better place to start working across identity divides.

So self, group, system, I think, is the trajectory that I work in and that helps us scale up from the small individual to a larger group to the whole social system that they're embedded in, and in this problem they're trying to solve.

A Powerful End

At the end of our discussion, I went back to Jay's observation that you don't work with people who are trying to tear the system apart, but rather work with people who already agree that working across lines of difference is a good thing to do. But I wondered, looking at the U.S. political conflict today, how do you find those people? So many people seem to have given up, including, I observed, many in our (the conflict resolution) field. As I said, so many people have thrown in the towel, and said 'the end is here. We are facing catastrophe." And in the face of that, they are doing things that 20 years ago, our field would never have countenanced doing, such as abandoning any attempt to act neutrally, and overtly taking sides (calling for the progressive definition of "justice," for instance, which then just fans the flames further). How do you get people who are in that kind of mindset, I asked, to switch to a notion that no, we really can do something valuable working across the political divide and we must do so in a way that doesn't presuppose a particular outcome. How do you take people out of the gloom to hope? Jay's answer was wonderful!

First of all, I think we have to be careful about language. So, when people say to me, “I'm optimistic,” I say, “whoa, I'm not.” Optimistic says” it will happen.” I say, “I'm hopeful, though.” Hopeful says “it could happen.” And then it also says, and “if it could happen, then I have some agency to try to help it happen.” I think when people are despairing, maybe it's because they were optimistic before, and now they realize that optimism was misplaced. And so, let's change them from being despairing, because their optimism was unfounded or destroyed, to hopeful for possibility.

And then from that hope, have a sense of agency. And the agency in our field is to say, “there are these extremists who are setting the agenda, and we're not going to join either side. Because if we do, then those in the middle who need to grow larger are not going to have our advocacy. Have the advocacy of our field.” . . .

And I think that's still the calling of our field, which is to have a sense of hope and possibility that things could change, and that if the people who are out there who may be despairing because it seems like the extremists are setting the agenda, help them not give in. And that we're not going to give in. Despite our own doubts, the state of our own fears, that we say, “we still believe deeply in the hopefulness of hope and in the possibility of possibility. And we're going to spend our energy building both-and solutions, building the common foundation on which we are constructing the future that we know is essential if we're going to survive.”

Jay had many more fascinating and important observations in this discussion that we don't have time or space to cover here. We hope you will watch the full interview or read the transcript, both of which are available at the link below.

Please Contribute Your Ideas To This Discussion!

In order to prevent bots, spammers, and other malicious content, we are asking contributors to send their contributions to us directly. If your idea is short, with simple formatting, you can put it directly in the contact box. However, the contact form does not allow attachments. So if you are contributing a longer article, with formatting beyond simple paragraphs, just send us a note using the contact box, and we'll respond via an email to which you can reply with your attachment. This is a bit of a hassle, we know, but it has kept our site (and our inbox) clean. And if you are wondering, we do publish essays that disagree with or are critical of us. We want a robust exchange of views.

About the MBI Newsletters

Once a week or so, we, the BI Directors, share some thoughts, along with new posts from the Hyper-polarization Blog and and useful links from other sources. We used to put this all together in one newsletter which went out once or twice a week. We are now experimenting with breaking the Newsletter up into several shorter newsletters. Each Newsletter will be posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please…