Pro-Democracy Efforts: the Tension between Power-Over or Power-With Approaches

Newsletter 155 - September 14, 2023

From Beyond Intractability's Co-Directors

Heidi Burgess and Guy Burgess

s the United States turns its attention to the 2024 Presidential election, its citizens are sure to encounter an increasingly forceful array of appeals for support from candidates and other groups claiming to be the "true defenders" of democracy. Citizens in other struggling democracies are, of course, likely to find themselves facing similar pressures. These competing claims, and the complex motivations behind them, are going to force those engaged in "pro-democracy" work to more clearly articulate what, exactly, they are trying to do, and how their work fits into this cacophony of voices. This essay is an attempt to shed some light on this important topic.

Competing Efforts to Save Democracy

Once thought to be humanity's best defense against tyranny and oppression, as well as dysfunctional chaos and policy failure, democracy is falling short of these goals and is seen as backsliding in many places around the world. Fortunately, a great many people are gravely alarmed about these backslides and they are devoting considerable time and energy to a variety of efforts to "save democracy." Unfortunately, since there is no consensus on what democracy is, or how it should be saved, many of these efforts are working at cross purposes. Our failure to reconcile these competing views is a big part of the reason why democracy is in so much trouble.

The Power-With vs. Power-Over Democracy Continuum

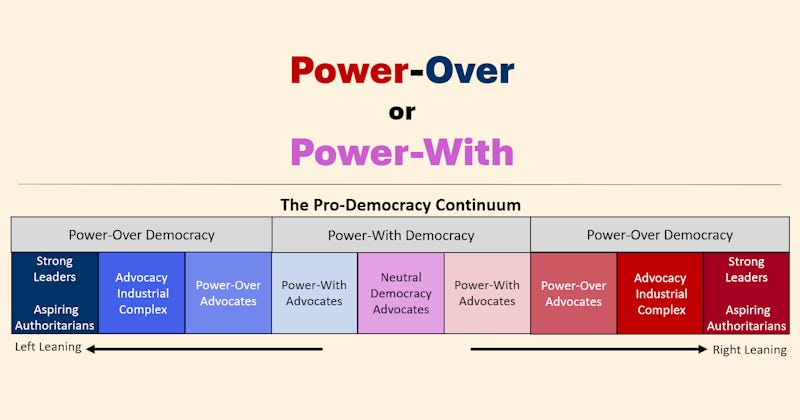

As we have tried to think through what distinguishes the various pro-democracy groups from one another, we have found it useful to think in terms of the above continuum — a continuum which combines the distinction between left-and right-leaning social aspirations with an important distinction between "power-with" and "power-over" visions of democracy.

The power-over vision sees democracy as a system through which citizens nonviolently decide who gets to make decisions on society's behalf, whose values are going to be favored, whose policy proposals are going to be implemented, and whose views and priorities are going to be pushed to the margins of society. Much of democratic political history is the story of competing efforts to build coalitions strong enough to overpower their opponents and effectively exclude them from the political process. While this may be a perfectly normal approach to hardball politics, it is also a way of practicing democracy that is responsible for a great many of the historical injustices that we now so vocally lament. These injustices are the natural result of the win-lose nature of this type of democracy and the "tyranny of the majority" that it revolves around. This system is also unstable. It forces contending coalitions to resort to increasingly extreme and desperate tactics to avoid winding up on the losing side of an extremely high-stakes zero-sum game — a process that has now driven the hyper-polarization spiral to the brink of societal breakdown in the United States.

Fortunately, there is an alternative to this sorry state of affairs. When they wrote all that inspirational language about freedom, equality, and the democratic ideal, the founders of U.S. democracy had a very different image of the system of government that they were designing. They imagined a power-with democracy in which a complex system of checks and balances would effectively prevent the kind of tyranny and authoritarianism that that they knew would result from the accumulation of unrestrained power in the hands of a few.

While still encouraging society's many interest groups to vigorously and freely argue for what they see as the most desirable social policies, a power-with system limits the ability of democracy's winners to impose their beliefs on their fellow citizens and exclude them from effective participation in the political process. It views democracy as a system that gives citizens living in very different circumstances with differing interests and values the freedom to live life as they choose — provided that they allow others to do the same. It is also a system that enables its diverse citizenry to work together on mutually beneficial projects including those that protect the commons on which everyone depends.

Power-Over Pro-Democracy Groups

If power-with democracy is so much better, then why are we locked in a power-over contest to see who gets to dominate whom? How might we escape this trap? A big part of the answer lies in understanding the motivations, actions, and interactions between of the seven different types of pro-democracy actors highlighted in the continuum diagram above. It is also important to understand that each of these groups of pro-democracy actors believes that they are genuinely trying to make things better and that their actions are clearly on the "right side of history." That said, there are doubtless genuinely sinister individuals who may be posing as pro-democracy actors, even though their real intention is to undermine democratic norms and institutions that they see as an obstacle to their efforts to accumulate wealth and power. It is important that these malicious efforts be distinguished from genuine, though sometimes misguided, efforts to advance democracy.

It is also important to understand the dynamics that lead well-meaning people to engage in activities that may well be counterproductive. These include, for example, the prisoners-dilemma problem — the likelihood that one side of a hyper-polarized political divide could find themselves in serious trouble if they were to unilaterally abandon hardball, power-over political tactics when the other side does not. There are also a variety of cognitive biases and communication distortions that lead people to unjustifiably dehumanize their political opponents and discount the validity of their arguments.

Power-over advocates tend to judge governmental institutions by their ability to solve what they regard as the big and, especially, existential problems that they see as facing society (such as climate change for the left or the runaway regulatory state for the right.) These groups (both on the left and the right) focus much of their energy on defending society from "the forces of evil" on the other side who, they charge, seek to impose their "immoral beliefs" on the larger society. If democracy, as it is currently constituted, is failing to solve these big problems, then these groups are likely to advocate changes to existing rules that would further empower their side — even if those changes would require violating core democratic principles that they previously would have supported.

Supporters of this power-over vision of democracy tend to be concentrated among those who are extremely confident that their views and the views of their group are the right ones and the views of the other side is unquestionably wrong. They tend to believe that anyone who disagrees with them must either be malevolent or so seriously misinformed and misguided that their preferences must simply be overpowered. While there are cases in which a truly objective assessment of the facts and core democratic values might justify such self-confidence, there are many more cases where the opposition includes people who are raising legitimate points — points that, at the very least, deserve serious consideration.

A big part of the reason why so many people are so convinced that their views must prevail is that modern communication technologies have channeled us into largely closed information ecosystems (a.k.a. bubbles) which continually reinforce our group's beliefs, while dismissing the views of the other side. What little information we get about the views of the other side tends to be carefully filtered in ways that focus on (and often exaggerate) the most outrageous and indefensible things that the other side is doing, while suppressing thoughtful and reasoned challenges to one's own group's behavior. This is psychologically attractive because spares us from the discomfort that comes from having to consider the possibility that we might, in some important way, be wrong.

Within the power-over segment of those who see themselves as doing, pro-democracy work, it is useful to distinguish (on both the left and right) the three subgroups highlighted in the above diagram: strong leaders and aspiring authoritarians, the advocacy-industrial complex, and power-over advocacy groups.

Strong Leaders/Aspiring Authoritarians

People who see politics as an us-vs-them struggle between good and evil tend to be drawn to strong leaders who are willing to do whatever it takes to defend their group and, it is assumed, the larger society. (This may, when the situation warrants, include dispensing with any democratic niceties that may be giving the forces of evil an advantage). Not surprisingly, those who embrace strong leadership in the pursuit of their political priorities are likely to view strong leaders pursuing opposing priorities as dangerous, aspiring authoritarians. On the left, as this article explains, there is widespread concern about what a second, more effective Trump Presidency might look like. On the right, concerns about widespread discrimination against those who disagree with prevailing "woke" orthodoxies have led to calls for a new Civil Rights Act. In many cases, it is these leaders who are seen as the principal threat to democracy and the target of the other side's pro-democracy efforts.

In the United States and elsewhere, the processes of escalation and polarization have intensified left/right animosities to the point where a great many of these strong leaders have emerged. These leaders have, in turn, exhibited a willingness to work around inconvenient democratic obstacles in ways that really do pose a serious threat to their political opponents (who have been thoroughly demonized and, often, dehumanized). They also threaten democracy overall. This willingness to bypass democratic safeguards has now reached the point where people on both sides feel so threatened that they are willing to use increasingly extreme measures to protect themselves and their interests. U.S. examples include the attempt to convince Vice President Pence to not certify Joe Biden's election on January 6, urging the Georgia Secretary of State to "find more Republican votes," gerrymandering to create as many "safe seats" for one side as possible, seeking to by-pass Congress by asserting increasingly broad Presidential powers and by appointing "interim" agency heads that don't need Senatorial approval, and clandestine and deceptive efforts to get the other side to nominate weak candidates that can more easily be beaten.

Many of these supposedly strong leaders are actually corrupt and unscrupulous individuals who are more interested in building their own power base than defending the interests of those whom they claim to represent. These genuine aspiring authoritarians (and the symbiotic media channels that support them) use a variety of hatemongering tactics to inflate the threat posed by the other side in ways that demonstrate the need for their "strong leadership." Sadly, this is a tactic that aspiring authoritarians have repeatedly used throughout history to undermine and, in far too many cases, destroy democratic systems of government. This is why so many pro-democracy groups are focusing their efforts on opposing and overpowering political coalitions that they believe have been captured by such individuals.

This means that we all need to cultivate an ability to distinguish between those who are genuinely trying to defend democracy from true authoritarian threats and those who are using (and sometimes inflating) those threats as an excuse for marginalizing and disempowering legitimate political opponents.

The Advocacy Industrial Complex

The United States (and other modern democracies) are now home to a vast array of powerful public interest groups which champion a vast and often competing array of political causes. These groups, which are staffed by an extensive network of volunteers and skilled professionals, have played a major role in forcing democratic societies to take significant steps toward addressing past injustices and solving other pressing social problems. The civic culture embodied by these groups is a big part of what makes problem-solving work in effective democracies.

That said, it is important to recognize that these advocacy groups are also vulnerable to the same conflict-of-interest problems that plague all large and entrenched bureaucracies. These organizations are almost always established to promote efforts to solve some serious social problem. Once the group succeeds in getting this problem addressed, its reason to maintain such a large-scale effort largely disappears (even though more modest efforts to sustain the progress made are usually warranted). Ideally, these groups would declare victory and either disband or reduce their size or, alternatively, reorganize themselves around some new and worthy objective. This, for example, is what the March of Dimes did when new vaccines put an end of the threat posed by polio. They refocused their efforts on combating birth defects.

Those working for advocacy groups need to honestly acknowledge when their primary objective has been achieved and move their attention to another equally worthy objective. Unfortunately, this can be difficult. There are often more people wishing to work in advocacy roles than society has figured out how to effectively use. Under such circumstances, there may be a temptation to overstate and demonize the reasonable actions of others as a way of "drumming up business." This is, obviously, quite divisive and tends to undermine the credibility of the groups that take that approach.

For example, in the environmental movement, we have seen a transition from efforts to oppose the most grotesque forms of environmental pollution (like the Love Canal toxic waste dump or Cleveland's Cuyahoga River which was so polluted that it caught fire four times) toward a focus on much more minor environmental issues that, to many people, constitute a vast regulatory overreach. Similar stories can be told about efforts to address occupational health and safety concerns or the blatant sexism and discrimination against women that was common in1950s and 60s. Successful efforts to address these problems have now reached the point where reasonable people can conclude the things have gone too far the other way. For example, see this article on the 5000 rules governing apple growing or this article on misandry (the opposite of misogyny).

Interest groups also need to guard against the temptation to constantly move the goal posts (pursue ever more ambitious objectives) so that whatever one's opponent does, it is never enough. If people believe that, no matter what they do, they will always be painted as evil and the enemies of progress, then they have little incentive to make perfectly reasonable changes in their behavior. Not surprisingly, this can produce the kind of backlash and cynicism that undermines public support for what otherwise would be a thoroughly worthy objective.

In short, those in advocacy roles need to guard against becoming just another self-perpetuating bureaucracy that sustains itself without really producing corresponding societal benefits. As one last example, it is easy to see why (as this article explains) so many people are suspicious of the current generation of anti-racism programs that, instead of offering a pathway to a post-racial society, argue that all whites are irredeemably racist, and that, therefore, there is a perpetual need for expensive diversity, equity, and inclusion programs (which, research has shown, do little to remedy racism, and may actually make it worse). To avoid this problem, we might want to consider proposals for a less divisive strategy such as the one being championed by the Foundation against Racism and Intolerance.

Power-Over Advocates

The last group of power-over advocates consists of people who see democracy primarily as a system that gives people who see a need for social policy changes an opportunity to build enough public support to get those changes implemented over the objections of those with whom they disagree. In practice, this is a lengthy and complex process that requires building mutually supportive (and often disagreeable) alliances with other groups with different interests. In hyper-polarized times, successful advocacy is only possible when the political alliance to which one belongs is in power. This means that a nuanced consideration of individual issues gets replaced with an all-encompassing confrontation between giant political coalitions on the left and the right. On the left, this is translated into efforts to advance a secular, progressive vision of social and environmental justice, while diminishing the influence of those with traditional, largely Christian beliefs. On the right, the focus is on pushing back against this progressive vision and restoring US democracy (with its traditional cultural values) to its former glory. Both groups are so deeply committed to their worldview that they find the prospect of compromise on these fundamental moral issues to be completely unthinkable.

Power-over advocates (on both the right and the left), not surprisingly, tend to favor democratic reforms that would strengthen their position, while opposing, often using anti-democratic rhetoric, any changes that might tilt the power balance in the other direction. When pressed, members of this group are also willing to embrace the above strong leaders — people who are willing to do whatever it takes to put society back on the "right track" (even if that means accepting a fair amount of corruption as just another cost of doing business). What counts are results (or, at least, perceived results).

The Collision of Power-Over Democracy Advocates

Those in the above three groups on both the left and the right (with the exception of a few cynical profiteers and aspiring authoritarians) believe that they are engaged in a noble battle to save democracy. Unfortunately, since the left and the right are diametrically opposed to one another, they are on a collision course that could result in one of two principal dystopian outcomes that we believe are the real threats to democracy. First, we could see an indecisive, but increasingly intense, dysfunctional, and destructive series of confrontations. Or, we could see one side emerge victorious with the power and the inclination to marginalize and oppress the opposing group whose demonized interests they feel they can ignore.

This suggests that, before continuing down this path, power-over democracy advocates ought to think long and hard about where this confrontation is taking us. They should particularly consider the many ways in which things might go very wrong with, for example, large-scale political violence or decisive defeat (instead of the glorious victory we tend to focus on). Power-over advocates also ought to consider the likelihood that the evil stereotypes they have of the other side might mostly be inaccurate products of our cognitive biases and inflammatory information environment. (Indeed, research shows this is widely true, with the most "informed," politically active people having the most inaccurate views of "the other." (See, for example More In Common's findings on "the perception gap.")

This raises several questions. One, is it really true that we have no alternative to, in effect, going to war with one another? Two, is there really no way that we can reverse the escalation spiral in ways that give us confidence that the other side will not take advantage of any conciliatory gestures we might make? And three, is there really no way in which we can agree to coexist with one another, despite our differences? Given the reverence with which the left views "diversity" and the right views "freedom," we ought to be able to find a way to do these things.

Power-With Democracy

In sharp contrast with the above pro-democracy groups and their power-over orientation, there is a second major group of pro-democracy advocates focused on defusing the above collision. This group views democracy primarily as a system for allowing people with very different moral beliefs, personal priorities, and worldviews to share power in ways that allow everyone to live together in a climate of respect, peace, and mutual support. Rather than trying to enforce some unitary definition of social justice and morality, advocates of power-with democracy seek to give everyone the right to live life as they choose, provided that they extend that right to others.

This group also realizes that, for democracy to succeed, it has to give those on the losing side of democratic decisions confidence that their democratic rights and freedoms will still be protected and that they will have the right to again argue their case in the next election. They also recognize that these rights and freedoms come with obligations — to protect the rights and freedoms of fellow citizens with whom one disagrees, and to help support and defend the commons upon which everyone depends.

The continuum diagram at the beginning of this article highlights two principal groups within this power-with democratic coalition.

Power-With Advocates

Much like the power-over advocates, power-with advocates are focused on trying to persuade their society to take the steps needed to solve some particular problem (or pursue some particular opportunity) that they view as especially important. While they believe that their assessment of the situation is accurate and that the prescriptions they offer are sound, unlike the power-over advocates, power-with advocates are willing to consider the possibility that they may, in some significant way, be wrong, and that others with different perspectives might have valuable insights and suggestions to offer. In other words, while they want to persuade others to adopt their view, they remain open to being persuaded to change those views—at least in part.

They also are willing to compromise and/or collaborate with the other side. Ideally, they will work together to identify ways to "expand the pie" and meet everyone's interests and needs at the same time. If that isn't possible, they are willing to compromise on some of their interests in order to fulfill some of the interests of the other side, while supporting the identity and security needs of everyone.

Power-with democracy advocates are also committed to supporting democratic decision-making processes and are opposed to subverting those processes for partisan purposes (even when it is to their own advantage). They understand that democracies are not flawless. Democracies are likely to make decisions that are unwise, inefficient, or unfair. Still, despite these flaws and the almost certain policy defeats that will occasionally accompany them, power-with advocates recognize that a functioning democracy is vastly preferable to the acrimonious, dysfunctional, and potentially violent confrontation between competing power-over factions. They also consider it far superior to the prospect of authoritarian rule, should one of these factions somehow gain the power needed to solidify its control over others.

Neutral or "Multi-Partial" or "Omni-Partial" Power-With Democracy Advocates

The final group of pro-democracy advocates consists of those who, at least for their pro-democracy work, try hard to put aside their personal policy preferences and devote themselves to defending and strengthening democratic norms and institutions that support everyone, and most importantly, democracy itself. While we used to (and often still do) refer to such people as third-party "neutrals," many of our colleagues argue that it is impossible for anyone to really be or act in completely neutral ways, as we all perceive the world with different sets of biases, from which we cannot escape. Though that is true, we still think that there is great value in striving for neutrality and that, at the very least, it is possible to deal with all people respectfully and fairly. However, we will also accept our colleagues' alternative terms of "multi-" or "omni-partial" to describe this group. They do this in both the self-interested and altruistic belief that a strong and functioning democracy offers the best means for guaranteeing that their aggregate interests (and the interests of their fellow citizens) will be protected.

Among the key objectives of this group are the following:

Oppose those who use democratic rhetoric as a smokescreen to disguise efforts to dominate and impose their will on the larger society. This generally involves some combination of efforts to persuade people to abandon their quest for social dominance, in favor of a more pluralistic and ideologically diverse society; changes to the societal incentives that make it harder for aggressive, power-over campaigns to succeed; and, for when that fails, direct opposition of those who seek power over everyone else.

Addressing past injustices in ways that acknowledge past wrongs and provide assistance to those who are still being unfairly disadvantaged, while also taking strong steps to limit ongoing and future injustices.

Building bridges that enable people on all sides of the political divide to move beyond today's hyper-polarized hostility and re-humanize one another in ways that promote mutual understanding and respect for differences, while also encouraging collaboration and joint problem-solving.

Building a stronger and more prosperous society that expands opportunities for all, while making progress on our important social, economic, and environmental problems.

Drawing the Line between Power-With and Power-Over Pro-Democracy Efforts

Deciding whether to pursue a power-with or power-over democracy can be difficult, especially in today's hyper-polarized political environment in which partisans on both sides believe that the other side constitutes an existential threat to "our democracy." Still, it is critically important that we understand when we cross the line that separates constructive, power-with, pro-democracy efforts from destructive, power-over efforts to impose our views on others.

One especially clear example of how this distinction arises in the day-to-day pro-democracy work among centrists and progressives centers around the debate over whether one should seek to build bridges to the other side (meaning Democratic/Republican or Progressive/Conservative) in an effort to reduce hyper-polarization, or whether one should focus on fighting for social justice (as the left defines it). Justice advocates generally say that if polarization remains the same, or even if it gets worse, that is acceptable, as it is the fight for justice that is paramount. This is, essentially, the debate which we were having a year ago with Bernie Mayer and Jackie Font Guzman in Newsletters 53, 54 and 55 with comments from others in Newsletter 56.

It is also playing out now in tensions between people who all think of themselves as democracy builders. Many people we have talked to over the last several months have been very supportive of and excited about the July 2023 22nd Century Conference and the ideas presented in its companion paper "Toward a People Powered Democracy" by James Mumm and Scot Nakagawa. This paper and conference called for a "block and build" strategy which would block the authoritarians from obtaining power, while building a democracy that corresponds to their progressive ideals.

Others, including us, see the language in the People Powered Democracy approach to be very partisan and hostile to conservative ideas — not just extreme, anti-democratic right-wing ideas, but most, if not all, conservative (and many moderate) beliefs and values. Therefore, we believe that the 22nd Century's progressive agenda would, depending on how exactly it's framed, alienate a very large fraction of the American electorate, and therefore, not only fail to achieve its pro-democracy objectives, but make the dangers of hyper-polarization (political dysfunction, constitutional crises, and, potentially, violence and constitutional crises) even more likely to come to fruition.

One of our colleagues has tried to address this issue by calling for a bridge, block, and build strategy — adding the notion of "bridging" to block and build. This might indeed be helpful, but it all depends on how big a bridge one is willing and able to build.

Though they didn't use the world "bridge," Mumm and Nakagawa's paper calls first for bringing together the various pro-democracy factions with the goal of creating a unified political coalition with the power needed to successfully oppose the anti-democratic aspirations of the opposing, right-leaning political coalition (led by former President Trump) that they see as both an imminent and existential threat to democracy (as well as to their largely progressive partisan interests).

The second part of the strategy focuses on using the strength of that political coalition to "block" the opposing political coalition from succeeding in its efforts to subvert democratic norms and institutions. They also seek to prevent them from obtaining power at all, so they cannot implement an associated array of policies on race, gender, climate, and other issues that the left considers indefensible.

Once this antidemocratic agenda has been decisively and, presumably, permanently defeated, Mumm and Nakagawa call for "building" a new "resilient and inclusive multiracial, feminist, and pluralistic democracy" that delivers what the largely progressive, Democratic promoters of the strategy think that democracy ought to be.

This is clearly a power-over approach. If the bridge is just big enough to garner the support needed to decisively win enough elections to reshape US democracy in ways that assure that their views will continue to prevail, then this is really nothing more than a naked partisan effort to overpower the political right. As such, it is certain to generate all-out opposition, the kind that will further drive the hyper-polarization spiral and force both sides to resort to increasingly desperate and anti-democratic tactics as part of an increasingly destructive conflagration — one that could easily destroy the democracy that everyone claims to be defending.

An expanded bridge building effort could, however, turn this strategy into a power-with approach. The key is making the bridging effort big enough to bring in conservatives who also seek to preserve and strengthen democracy and do so in a way that leaves room for them to live their lives as want to, as long as they (the conservatives) allow the progressives to do the same. This approach would reach out to people who think that white Christian men deserve a seat at the table as much as nonwhites, non-Christians, and women do, and believe that they should be given just as much voice in the conversations about how to "save democracy" as the other groups. It would need to reach out to people who believe that there are only two sexes, that preadolescent children should not be transitioned to a different gender, and that abortion is murder, because a fetus is a human being.

Such an approach would be much less likely to engender widespread opposition or increase hyper-polarization. And it would be more likely to make progress on the goals all sides want: a respected identity for whomever they are, and security (both physical and psychological), which means safe communities, good jobs, stable incomes, stable climate, etc.) The only people to be excluded from such an expanded bridge building effort would be those who steadfastly seek to apply a double standard that privileges their group while marginalizing others. To be successful, this kind of bridge building would doubtless require building a coalition capable of working through a lot of tough issues about what, exactly, constitutes fairness going forward and how to deal constructively with the many injustices of the past.

Conclusion

While we, personally, have strong views in favor of the power-with approach, we recognize that there are many who disagree vehemently with our point of view and believe strongly that the threat posed by rebellious populists on right or arrogant and corrupt elites on the left is so serious that they must be unequivocally defeated.

The conflict between these two broad points of view is one of the most consequential facing contemporary society. It really matters whose view of the truth turns out to be most accurate and which strategy for strengthening democracy we collectively decide to pursue. If ever there was a case that calls for respectful debate and the careful consideration of competing arguments, this is it.

So, despite our differences, we respect the fact that others may have very different views on this important topic and we promise to continually reassess our views as we hear from others. We also plan to continue to use Beyond Intractability as a platform for exchanging thoughtful reflections on this issue. So if you, our readers, have thoughts on these issues, please share them. We will gladly publish everything we get that isn't overtly malicious, including essays that disagree with us, as we still believe that conflict is the only way we learn, and the conflict between the power-with and the power-over advocates is one that can teach all of us who want to help "save democracy" how to do so more effectively.

Please Contribute Your Ideas To This Discussion!

In order to prevent bots, spammers, and other malicious content, we are asking contributors to send their contributions to us directly. If your idea is short, with simple formatting, you can put it directly in the contact box. However, the contact form does not allow attachments. So if you are contributing a longer article, with formatting beyond simple paragraphs, just send us a note using the contact box, and we'll respond via an email to which you can reply with your attachment. This is a bit of a hassle, we know, but it has kept our site (and our inbox) clean. And if you are wondering, we do publish essays that disagree with or are critical of us. We want a robust exchange of views.

About the MBI Newsletters

Once a week or so, we, the BI Directors, share some thoughts, along with new posts from the Hyper-polarization Blog and and useful links from other sources. We used to put this all together in one newsletter which went out once or twice a week. We are now experimenting with breaking the Newsletter up into several shorter newsletters. Each Newsletter will be posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please…