.Note: All our newsletters are also available on the BI Newsletter Archive

I was recently working on finding resources for our soon-to-be-released Constructive Conflict Guide, and one of the topics that was in need of more readings was the section on core and overlaying conflict factors. I had several things that were written by us, but since, when we tell people about this distinction, they seem to find it useful, I was curious to see if anyone else had picked up on this idea and written about it.

As I have been doing recently, I asked my new, eager, research assistant, named ChatGPT, to find articles that other people had written about this distinction. It told me that I was right, that the Burgesses had written "quite a lot about that," and so had other people, although "they used different terms." When I looked at the citations though, I found out that the terms other people used really weren't talking about the same thing. So I came to the conclusion that no one (at least that ChatGPT could find) has picked up on this distinction.

I decided that it might be useful to do a newsletter on it, and then I found we had one already, published in February of 2023. Since that was two years ago, and we've gained many readers since then, we thought we'd reprise and update that newsletter, in the hopes that some of our new readers might find the distinction useful. And, since we are once again attempting to make our newsletters shorter (easier for us to write and easier for you to read), this time we are spreading this over two newsletters, this first one looking at core conflict factors, and the next one looking at overlaying conflict factors.

The Core/Overlay Distinction

Much of our new Constructive Conflict Guide will be focused on helping people engage in hyper-polarized and intractable conflicts more constructively. One of the first steps in doing that is getting as clear an understanding as possible about what is really going on. Hyper-polarization causes most people to greatly oversimplify their definition of the problem into one of "us-versus-them," "good guys-versus-bad guys." The assumption, further, is if "we" could just "get rid of them," or convince them "we" are right, or disempower "them," so that they can't cause any more "trouble," or "regain power in the next election," then everything will be fine. Of course, it never is, because "they" think of "us" in just the same way.

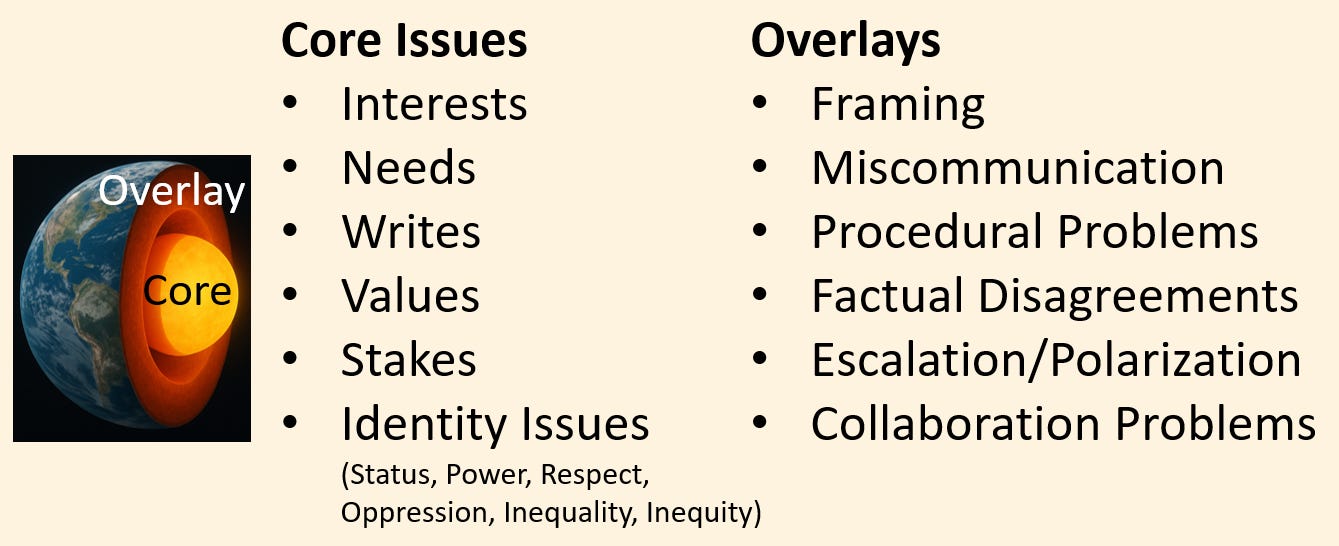

So, we urge people to "complexify" their understanding of the conflict(s) they are concerned about. To do this, we suggest that people try to identify both the core issues of disagreement, and what we call the "overlaying" issues or "complicating factors," a synonym we developed when we were doing a lot of training of people for whom English was not a native language..

These terms overlay and core are based on a geological metaphor, looking at the core of the earth and the rock layers on top of the core, which geologists call "the overlay." The core of the earth is small, deep, and very hot, just as the core of intractable conflicts is often very deep-rooted and very "hot." Though the conflict core is not necessarily small—it can be about very big and important issues (the parties' interests and needs, rights, moral beliefs and values, identity, security, and what we call "high stakes distributional issues"), it is not nearly as big as it gets when the many "overlay factors" get added on top of it. Those overlay factors are all the "stuff" that gets piled on top of the core that obscures the core conflict so much that sometimes you can't see it at all. (Examples, which we'll talk about more below, include misunderstandings, factual disputes, procedural problems, escalation, polarization and other "complicating" factors.

Core Conflict Factors:

Core conflict issues are the things that the conflict is fundamentally about — factors such as interests, needs, rights, values, stakes — particularly high stakes — and identity issues — including status issues, or power, respect, oppression, inequality, and inequity. Let me talk about each of these in turn.

Interests

Bill Ury and Roger Fisher (with Bruce Patton in the Second Edition) of Getting to Yes came up with the distinction — or I guess I should say they popularized the distinction — between interests and positions. It's a distinction that others had made before, but they made it well-known. Interests are the desires or goals, the things that you really want out of a conflict, as opposed to positions, which are much simpler statements about the policies that one favors or opposes. So positions seem to be simple — I want this, I want that, I favor this, I favor that — where interests are more nuanced. "I want this because..." and the reasons often yield insights about the way interests are negotiable and potentially win-win, when positions tend to be in opposition and zero-sum. (The classic way of teaching this distinction is to tell a story about two children fighting over an orange. The unenlightened mom cuts the orange in half and gives one half to each child, according to their positions "I want the orange!" But the conflict-savvy mom asks them why they want the orange. One child says she wants to eat it, while the other wants the rind for an art project (their interests). So, she peels the orange, gives the rind to one, the flesh to the other, and they both get 100% of what they want. Put another way, particular positions are just one way of pursuing one's interests. Unfortunately, we tend to fixate on such positions as the only way in which we can get those interests met. This neglects the possibility that there are other ways of pursuing those same goals — ways that are less likely to generate opposition and more likely to become part of some mutually-acceptable agreement that gets us more or even all of what we wanted.

Needs

There are another kind of interests which are much more fundamental. Those are what John Burton and other human-needs scholars refer to as "fundamental human needs". Needs are related to interests, but they are so important that they are seen as non-negotiable. The needs that are most often discussed in terms of conflict and conflict resolution are identity, security, and recognition.

People don't negotiate who they are. They don't negotiate whether or not they feel secure. They don't negotiate whether they're going to be recognized as a legitimate, respected, honored person or demographic group. So, when people feel threatened, when they feel humiliated or diminished, when they feel insecure, John Burton and other human needs theorists observed that they tend to fight back. And they continue fighting until their needs are met.

This is why we are so concerned about the tendency of the progressive left to humiliate and threaten people on the right who they label as "racist" or "oppressors." Many diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) trainings, for instance, try to force whites to acknowledge their "privilege," implying that it is undeserved, and that they should feel guilty and lessened by that discovery. Human needs theory makes it very clear that such an approach is not likely to win friends or allies. Rather, it is more likely to strengthen opposition to the progressive goals and create enemies out of people who might have otherwise been supportive of DEI. Donald Trump's attempt to dismantle DEI programs in both government and private enterprises is an illustration of what tends to happen when people feel humiliated. He is lashing back, on his own behalf, and on the behalf of his many followers who also feel humiliated by the labels "privileged," "racists" and "oppressors." It is, of course, also true that those on the right use similarly disrespectful and threatening language in ways which reinforce antipathy on the left. The result is a situation in which neither side wants to meet the needs of the other.

So it is important to recognize that everyone has needs and they feel those needs just as strongly as anybody else. The progressive left has long recognized the damage that has been done to oppressed communities — people of color, LBGTQ+ members, etc. They have long recognized that these groups need to be given respect; they need to feel secure in who they are and how they fit into their communities. But turning the table and denying the legitimate identity and security needs of people who have been labeled as "oppressors"— often through no fault of their own — is not going to bring equality, and it is not going to bring peace. It is just going to bring continued destructive, hyper-polarized conflict.

Rights

In addition to needs are rights, which are independent standards of fairness that are either socially recognized or formally established in law or in a contract. There are the fundamental human rights that are now included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including such things as life, liberty, security, and a number of other rights that are delineated in laws and constitutions.

The United States has a Bill of Rights that includes most of what is in the fundamental, universal human rights but also has things such as freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and the right to bear arms. The latter two, of course, are strongly contested. So, too, is the abortion issue, which was framed as a "right" in Roe v. Wade, but was seen by many (including by progressive juror Ruth Bader Ginsberg) as a badly framed opinion which was so obviously flawed that it led to endless conflicts over its legitimacy, culminating in its reversal in 2022 with the subsequent Dobbs decision.

Just like needs, rights are non-negotiable. If you have a right, then others have to respect that right, regardless of how much it costs them. That is why Mary Ann Glendon observed in her book Rights Talk, that we have more and more groups asserting more and more rights. If people believe they have those rights, they will fight for them, either through legal mechanisms or, if legal mechanisms don't work, extralegal mechanisms, including, at times, violence (as has been quite common in the abortion controversy). Glendon's point, with which we agree, is that when you frame things as "rights," you make them non-negotiable, thereby making the conflict surrounding them intractable. If you frame the same issue as an interest, you are in a much stronger position to negotiate, and you might well get more of what you wanted than you could get by framing it as a right that gets forever contested.

Values

Values are fundamental beliefs about what is right and wrong, good and bad. On important issues, people don't negotiate these either. They stick to their values, and they try to convince other people to follow their values (because, to them, those values are "right" (meaning correct and virtuous) and others are wrong or even evil). And if they can't convince others to observe their values, they fight very hard so they, at least, are allowed to follow their own values, even if others don't. When we initially wrote our essay on core and overlay, we talked about the conflicts over gay marriage and abortion as value conflicts. They still are, but it is interesting to observe how quickly values on gay marriage have changed, and how little change has occurred in the conflict over abortion. Examining the difference here is outside the scope of this essay, but it is a comparison that is well worth making, as it can teach us a lot about ways to pursue social change and ways not to.

High Stakes

Another thing that contributes to intractability are the stakes of a conflict. If they're very high, if they're life or death or millions of dollars at stake, people are going to fight much harder. And they're going to be much less likely to compromise. If it's not a big deal, if you go, "ehh, I don't care," then it's not going to be an intractable conflict. You can resolve it pretty quickly. This, again, is why the conflict over immigration is so entrenched. People who are lower on the economic hierarchy tend to see immigrants as threats to their jobs. People who are secure don't worry about that.

All of the core factors I listed above (with the exception of interests, which are often negotiable if one focuses on them instead of positions) are things that tend to make conflicts very deep-rooted and intractable. Unfortunately, though, they are usually made even more difficult by the various overlay factors that obscure the core issues and make them much more difficult, sometimes to see, let alone to address successfully.

Given that we are trying, once again, to make our newsletters shorter, we are going to stop here, and talk about the overlaying conflict factors in another newsletter, coming out shortly.

About the MBI Newsletters

BI sends out newsletter 2-3 times a week. Two of these are substantive articles. Once a week or so we compile a list of the most interesting reading we have found related to our topics of interest: intractable conflict, hyper-polarization, and democracy, and we share them in a "Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links” newsletter. These links include articles sent by readers, information about our colleagues’ activities, and news and opinion pieces that we have found to be of particular interest. Each Newsletter will be posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please ....