.Note: All our newsletters are also available on the BI Newsletter Archive.

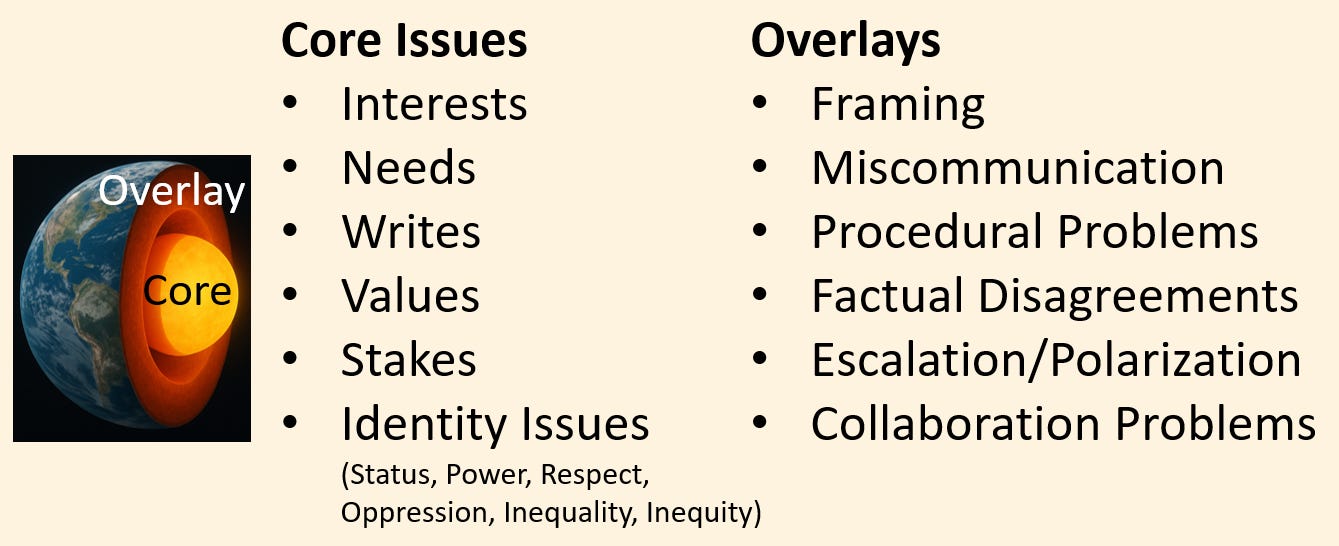

This is a continuation of our last post which explained our distinction between core conflict factors and conflict overlay factors. In the last post, we described the most common core factors, and explained why they tend to make conflicts so difficult to manage. We shared a little bit about what can be done to address them more effectively, but much more on that will be coming soon, after we deploy our new Constructive Conflict Guide. Now we want to explain what we mean by "conflict overlay factors," which are factors other than the core issues in dispute, which tend to make conflicts much more difficult to deal with. Fortunately, these factors are also much easier to reduce or even eliminate than are the core factors, as we explain below.

Conflict Overlay Factors

Overlying the difficult issues at the core of all intractable conflicts are a series of overlying conflict problems that commonly make the conflict (and its component disputes) much more difficult to handle in wise and equitable ways. Sometimes these overlying problems can be so severe that they largely obscure the core issues and emerge as the primary focus of the conflict. We identify six such issues:

Framing difficulties that make it hard for people to see and focus on the core issues;

Miscommunication and misunderstandings that undermine the ability of the parties to successfully communicate their motivations and actions;

Procedural problems that arise when people distrust or are unable to navigate the process through which a dispute is being addressed;

Factual disagreements which arise when the parties can't agree about the objective realities associated with a conflict problem and its possible solutions;

Escalation and polarization which can transform mutually beneficial problem-solving into unthinking hostility and a desire to hurt one another; and

Collaboration problems that make it difficult or impossible to work with other disputants to find mutually-acceptable solutions to mutual problems.

Framing

The first overlay we talk about a lot is destructive framing. Framing is the way that we make sense of the staggering scale and complexity of the world in which we live. We are simply not smart enough to think about everything, so we make broad generalizations and use those generalizations to guide our opinions and behavior. For instance, we categorize people, information, and actions as good or bad, right or wrong, helpful or not helpful, beautiful or ugly, etc. The problem is not with framing itself, but how it interacts with other people's frames and how it distorts our images of reality in ways that lead us to do things that undermine, rather than advance, our interests.

Americans live in such different geographic, socio-economic, philosophical, and moral "places" now, that any information we take in gets filtered by frames that reflect our biases and worldviews. For example, many people on the left judge information according to the "oppressor/oppressed" and the "diversity, equity, and inclusion" (DEI) frames. This view tends to see US history as a long chronicle of oppression in which marginalized groups (primarily defined in terms of race, gender, religion, and sexual orientation) have been exploited by privileged white, male, Christians. To those who subscribe to this frame, contemporary politics is a reckoning and an attempt to bend the arc of history in ways that would eliminate and perhaps reverse this regrettable, historical privilege. Anyone or any program that contributes to such ends is seen as "good." Anyone or any program that questions or detracts from such ends is seen as "bad."

In contrast, many people on the right feel that the DEI movement has gone too far, is guilty of "reverse discrimination," and has now reached the point where it is destroying much of what made, in their view, America the greatest nation in human history. This is the "Make America Great Again" (MAGA) frame. The movement that this frame motivated is now, under Donald Trump, doing all that it can to reverse the many changes previously implemented by Democratic supporters of the Oppressor/Oppressed-DEI frame.

While this is obviously a simplification of a much more complicated reality, this way of looking at things does much to illuminate the contradictions and the irreducible win-lose nature of these frames. As long as this is how most people think about politics, there will be little hope of bridging what divides us. To do that, we will need a different frame. As we see it, the most promising possibility (which we have repeatedly advocated for in this newsletter), focuses on replacing the current us-vs-them frames (such as oppressor-oppressed/DEI and MAGA frames) with a more compromise-oriented, "Democracy For All," or "power-with" (as opposed to "power-over") frame.

Miscommunication/Misunderstanding

The above incompatible frames have arisen and are reinforced by the misunderstandings that arise because of the difficulties we have in communicating with one another in ways that build mutual understanding, trust, and respect. When frames (or worldviews) of competing groups are very different, the stage is set for fundamental misunderstandings and miscommunication. One person may say something that they think is completely innocuous and non-controversial and another, who has a different worldview, will see it as a serious insult. An example of this is what has come to be known as "micro-aggressions." For instance, when I was teaching, I usually asked my students on the first day of class "where were they from"? I was genuinely curious, particularly because I was teaching about international conflict. So it was very educational for me and for the students if we had people in the class from countries that we were going to be discussing. I later found out, however, that some people see the question "where are you from?" as offensive, as it implies to them that they are "different," that they don't belong here. As we self-isolate into communities of people who are very much like ourselves, and we read and watch things on social media and traditional media that reinforce our worldviews, rather than challenge them, the frequency of misunderstanding what "the other side" thinks, believes, says, or does becomes significantly higher. And this then reinforces our negative stereotypes and our enemy images of the other.

This, of course, is just one of the many dynamics that undermine our ability to communicate effectively. Other problems arise in the course of often awkward interpersonal interactions, while still others arise because of problems in the way that today's high-tech, society-wide information system operates. Examples include the algorithms that determine what social media posts we see and "narrowcast" newspapers, radio, and television stations and programs that focus on giving relatively narrow audiences the information that they would like to hear (even if it's not accurate). Beyond this, there are difficulties associated with our ability to speak clearly and listen well (especially when we are angry or fearful).

Procedural Problems

Another overlay factor is procedural problems. All organizations, communities, and nation states have set procedures for how they deal with contentious issues and policies. But when these procedures are seen to be unfair or unevenly applied, this can exacerbate conflicts. Immigration is a good example of this. (I find it interesting that I'm revising an article written in 2016, which used immigration as the procedural example then too. It's been an intractable issue for a long time.) Most people in the United States agree that current immigration policy is not fair, not efficient, and is not being applied evenly. (And, we should note, this was true long before Trump took office, even the first time.) In recent years, the system has been stressed far beyond the breaking point as huge numbers of would-be immigrants showed up at America's southern border everyday. (Trump has succeeded in stemming this flow, but at what cost?) When they are turned away without any consideration, the would be immigrants (and many progressives) in the United States get very angry. When they are allowed in (or they manage to sneak in illegally), conservatives are in an uproar. What should the process be? How can we manage the press of would-be immigrants fairly (both for the immigrants and the larger society)? This is just one of a great many examples of procedural injustice — the failure to give everyone the right of due process and equal protection of the laws. The polarization seizing our politics is such that we cannot even consider such issues; we just use them as political footballs in electoral rhetoric.

Factual Disagreements

Factual disagreements are a fourth overplay factor. What is true? What is a "fake fact"? The term "fake fact" was flying all over the place during the first Trump administration, and while it's not in the news as much anymore (at least it seems so to me), we are still having a lot of trouble finding trustworthy (and trusted) answers to a wide range of important factual questions. Take vaccines. To what extent do vaccines help prevent serious illness and death, and what are the risks of taking them? Some people say they help a lot, others say they are dangerous, causing (for instance) autism in children. Some people think the mRNA vaccines, first developed for COVID, are a miraculous godsend; others think they are an inadequately tested experiment. We now have a "vaccine skeptic," Robert F. Kennedy Jr, running the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, spreading distrust and fear about vaccines and medical research more generally to an already anxious population. What is missing and what is desperately needed is a widely trusted mechanism for resolving such disputes.

Factual disagreements are key in the climate debate as well. How much of a threat is climate change now? How important is it that we give up fossil fuels — and how fast? Will such changes even help, or are we over some "tipping point?"

Joint fact finding (plus, unfortunately, a lot of money) could help sort out these questions. Sadly, we prefer to use these factual disputes as political footballs too, to help get our side elected. Learning the truth and designing policy with respect to such truth is not something we seem to care much about.

Adding to the problem is the prevalence of fake science. Many journals are reporting that they are getting flooded with fake papers, and faked data in real papers is also not uncommon. That intensifies the public's distrust of "science" and adds to the notion that it is entirely impossible to figure out what is actually "true."

Escalation and Polarization

A fifth overlay is escalation and polarization, which, though different, go hand in hand. Conflicts go from minor disagreements to major conflagrations as the size of the conflict increases (in terms of numbers of parties, issues, and resources expended). Issues go from specific to general (until both sides simply hate and distrust everything the other side is and does). Tactics go from light to heavy (eventually reaching large-scale violence). And, finally, the parties' goals go from meeting one's own needs (doing well) to doing better than "the other" to simply hurting "the other," even if it hurts one's own side as well.

Polarization is a coalition-building process in which interest groups recognize that the only way that they can successfully defend their interests is by forming alliances and agreeing to fight on behalf of others (in return for their support). This makes it hard to make peace with respect to particular issues, since coalition partners are now obligated to continue the fight on each other's behalf. The constant effort to defend (and advance) the many interests of the coalition also sets off an arms-race dynamic that leaves both sides feeling that they have no choice but to devote increasing resources to the conflict and to use ever more extreme tactics. The resulting positive feedback loop is how escalation pushes societies toward catastrophe (and away from good-faith efforts to address core issues).

Collaboration Problems

Collaboration problems are an off-shoot pf all of these other overlays, but particularly of zero-sum or win-lose framing. Disputants often believe that they cannot get what they want, unless they take it from “the enemy.” They assume that any “win” for their opponents is necessarily a “loss” to them, and vice versa. The wins and the losses always add up to zero, hence the name “zero-sum” framing. In many cases, this means that disputants don’t even try collaboration, because they don’t want to take the risk of having to give up something. Alternatively, they may try collaboration, but then work in any of a number of nefarious ways to undermine the process, such that they either “win big,” or the process fails entirely.

Another common problem is that people assume that they cannot collaborate with “the enemy,” because they will be perceived by their own side as being weak, or being a “traitor.” People who suggest compromise or collaboration are often denounced; hence, there is a reluctance to do that, even when possible areas of agreement and potential win-win outcomes are evident.

Conclusion

All of these overlay factors tend to feed back upon each other, making each of them more intense, and more intractable. And, most importantly, they make the core conflicts seem bigger than they really are — often "existential." The result is that the only thing people focus upon is the need to win decisively (not compromising on anything). When there are people on different sides (two or sometimes more) who feel just as strongly about the conflict, but in oppositional ways, the end result is profound intractability, often accompanied by a growing risk of violence and other seriously destructive tactics. And those occurrences further decrease the likelihood that either side will be able to protect its core interests.

What To Do About All of This?

As we have said often before, and will be reviewing again as we present our Constructive Conflict Guide, we think that the most constructive approach to difficult and intractable conflicts starts by figuring out what is really going on. We tend to greatly over-simplify our understanding of such problems, turning them into simple us-vs-them, good-guys-vs-bad-guys narratives. It is almost always much more complex than that.

In our 2023 core/overlay post, we presented a "Core/Overlay Analysis Chart." People trying to develop a strategy for addressing any difficult conflict can go through this chart and try to fill out as many of the cells as possible. This can serve as a useful planning guide for people working to advocate for one side or the other, and a tool that could be used by facilitators or mediators, trying to help parties to understand their situation more clearly and then consider ways of diminishing the various overlay factors and then more constructively addressing the core issues.

In our upcoming Constructive Conflict Guide, we will be exploring these core and overlay factors in much more detail, highlighting how they can be avoided or diminished, and what can be done to address them constructively. So if this seems daunting, stay with us over the coming several months. We will be exploring all of this, and more!

About the MBI Newsletters

BI sends out newsletter 2-3 times a week. Two of these are substantive articles. Once a week or so we compile a list of the most interesting reading we have found related to our topics of interest: intractable conflict, hyper-polarization, and democracy, and we share them in a "Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links” newsletter. These links include articles sent by readers, information about our colleagues’ activities, and news and opinion pieces that we have found to be of particular interest. Each Newsletter will be posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please ....