CRS Did the Impossible. Now It Is Gone. Can Anyone Else Fill Its Shoes?

Newsletter 404 - December 1, 2025

In this newsletter we talk about the recently closed U.S. Community Relations Service, why its closing matters, and how we are trying to keep its memory — and more importantly, the knowledge and skills of its conciliators and directors — alive. In that regard, we are announcing the debut of Phase II of the Civil Rights Mediation Oral History Project. In 2002, we completed the first phase of this project, which involved extensive interviews with nineteen CRS conciliators and regional directors. The second phase started in 2021, and so far has added 11 new interviews. The new material has now been added to the original website, which has been updated to integrate both sets of materials. We will be holding a launch event for the new website with our partners Grande Lum, former CRS Director and now Director of the Martin Daniel Gould Center for Conflict Resolution at Stanford Law School, and Bill Froehlich, Director of the Ohio State University Divided Communities Project on Wednesday, December 3, 2025, from 12:30–2:00 pm EST. We hope you will join us!

About CRS

The Community Relations Service (CRS) was established in 1964 as part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Initially housed in the U.S. Department of Commerce, it was transferred to the Department of Justice in 1966, where it remained until President Trump closed it down entirely in the fall of 2025.

As laid out in the Civil Rights Act, its purpose was to “to provide assistance to communities...in resolving disputes, disagreements or difficulties relating to discriminatory practices based on race, color or national origin.” In 2009, its mandate was expanded by the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act to include alleged hate crimes committed on the basis of religion, disability, and gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation.”

Over the years, its staffing ebbed and flowed, typically being better funded under Democratic administrations than under Republican ones. Yet it remained in operation under many Republican administrations until President Trump closed it down completely (through a total “reduction in force”) in the fall of 2025.

(As I type this, there are a couple of lawsuits challenging the shutdown, so it is possible CRS will come back to life. At best, however, it will be a shadow of its former self, at least until a new administration comes to power that realizes the value that the agency provided to both the government and to America as a whole.)

Why We Say CRS “Did the Impossible.”

In 1998, a former CRS conciliator and regional director, Dick Salem, came to us, saying that CRS was moving its offices, and in the process, was discarding many files that he thought were essential to preserve CRS history. He wondered if we could store the documents at the Conflict Information Consortium Offices, rather than allowing them to be lost or destroyed. At the time, we hadn’t heard of CRS, so we asked him what it was and why he was so concerned.

Dick told us about CRS’s history and about its strong record of successfully mediating serious racial conflicts around the country.

This was intriguing to us, to say the least, because we’d been studying, teaching, and writing about intractable conflicts for quite a while, saying they usually “couldn’t be mediated,” or at least “they couldn’t be resolved through mediation.” And we often gave racial conflicts as an example of the kind of “intractable conflict” we were talking about.

So, looking at it superficially, either we were wrong to assert that, Dick was wrong to say they were successful — or we were defining “success” differently. We wanted to find out which it was.

After considerable deliberation, we decided that storing the CRS documents in our offices wasn’t practical and wouldn’t result in sharing the documents with people who might benefit from them. It also wouldn’t result in answering our question about “who was right?” So, we developed another idea.

We decided to do oral histories with current and past CRS conciliators, getting them to tell detailed stories about what they did and how. This would save the knowledge (and more) that might otherwise be lost when the documents were destroyed. And it would make CRS skills and services much better known than they otherwise would be. (Part of CRS’s mandate was to conduct its work “in confidence and without publicity.” That confidentiality clause led CRS mediators to avoid the press when possible and say little of substance when confronted by the media. The clause also made it difficult for researchers to dig into CRS case files. So little was known about the magic they worked outside of the agency. This seemed like a remarkable opportunity to change that.

Because of the confidentiality clause (and perhaps for other reasons as well), the director of CRS at the time told his conciliators not to talk with us. But we were free to talk to retired conciliators and regional directors, and a few acting conciliators agreed to talk with us anyway. In all, we interviewed nineteen people during Phase I, each for three, two-hour interviews. We gave them the opportunity to delete anything in the transcript that they later felt uncomfortable about (to help with confidentiality concerns) and Dick Salem, the project director) asked that we not post the original audios, so the transcripts were all that went public for Phase 1.

In 2020 or so, we got a call from Grande Lum, who had been the Director of CRS from 2012-2016. We were delighted to learn that he knew of the oral history project, and said that he’d found it very useful as he was preparing to take over the director role. He wondered whether we would be interested in doing more interviews with recently retired CRS folk.

We were very interested, as was Bill Froehlich, the Director of the Ohio State Divided Community Project, of which Grande is also a part. So the three of us teamed up to create Phase II of the Oral History Project. For this phase, we were able to do video interviews. We followed, roughly, the same interview questionnaire, adding in some new questions that weren’t applicable in Phase I. (For instance, this time we asked about the impact of social media and cell phones, which didn’t exist when we did the first interviews.) We again did, usually, six hours of interviews per person (though some ran long and others short), and we have interviewed (so far) eleven new people.

We have now finished transcribing and coding all of those interviews, and we have updated the original website to include the new material. As we said above, we will be holding a launch event for the new website in a zoom webinar with Guy and me, Bill and Grande, on December 3, at 12:30 - 2 EST. We will talk about the project, and how the output can be used by people interested in learning about how to better prevent and deal with racial conflicts and other potential hate crimes. Please register here to get the zoom link. (It is free!)

So, Who Was Right?

We came to the conclusion that both Dick and we were right, and it was more a matter of how you define “success.” Obviously, CRS did not make racial conflicts in this country go away. Nor did they make conflicts of religion, disability, or gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation” go away. Those are, as we said, intractable. But they did resolve hundreds, probably thousands of disputes relating to those subjects.

What is the difference? We use the distinction made years ago by conflict theorist John Burton. “Disputes,” Burton said, are short-term disagreements that are relatively easy to resolve. Long-term, deep-rooted problems that involve seemingly non-negotiable issues and are resistant to resolution are what Burton referred to as “conflicts.” Now, the unrest following George Floyd’s or Trayvon Martin’s murders, or the many other such events were not “relatively easy to resolve.” They were terrible events that unleashed extensive responses — much nonviolent, but some violent. But, still, those responses were time limited. We are not still marching in the streets over those (we’re marching for other reasons now). While CRS wasn’t solely responsible for cooling those situations down, they certainly helped.

In his description of CRS activities that Dick Salem wrote for Phase 1, he said:

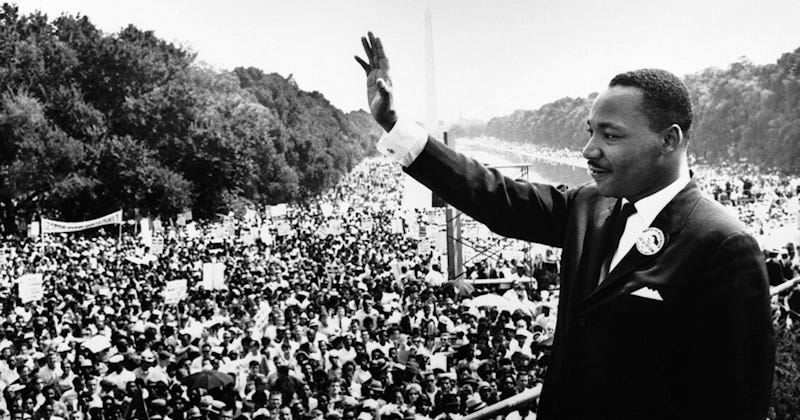

During the past 35 years, CRS mediators and conciliators have responded to thousands of volatile civil rights disputes, including virtually every major racial and ethnic conflict in the USA that surfaced during that period. CRS was present at the landmark civil rights march in Selma, Alabama in 1965 and its mediators were in Memphis, Tennessee three years later when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. CRS had a major presence throughout the 73-day takeover of the Village of Wounded Knee at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1973. And more than twenty CRS mediators and conciliators were in Los Angeles helping to mitigate tensions following the riots triggered by the Rodney King verdict in 1992.

CRS mediators worked in virtually every court-ordered school desegregation case in the nation in the 1970s, and in numerous prisons that were disrupted by racial conflicts. They responded to hundreds of communities racked by volatile and often violent police-community conflicts. They worked on dozens of Native American reservations, in the fields of California during the grape boycott led by Hispanic migrant workers, and they responded to Haitian, Asian American and Cuban refugee crises.

They continued to do this for the following 23 (or so) years as well, although their staffing levels were seriously diminished in the first Trump administration, and even more seriously cut in the second, before they were entirely zeroed out with the government shutdown that occurred in October-November 2025. So their ability to respond to every significant event was diminished in the last several years. But they still tried to respond as much as they could.

After listening to their stories, we were amazed at how successful the CRS conciliators were. They were usually able to get very angry, deeply wronged minority communities to trust and work with them, while also getting the powerful (usually white) sheriffs, police chiefs, school superintendents, and other “authorities” to trust and work with them at the same time. They succeeded in getting people “to the table” — sometimes literally for mediation, and sometimes metaphorically — on the street. They got them to calm down, to listen to and talk to the CRS conciliators, and often, the people “on the other side,” to work out agreements about how to move forward without violence, distrust, fear, and hate. They started lots of working groups, citizen oversight committees, collaboration committees — new structures that gave the minority communities a voice in authoritative processes (local governments, criminal justice entities, schools and school districts, etc.) going forward.

All of this is documented extensively in the Phase 1 and Phase 2 interviews. In addition, all the Phase 1 materials were coded, and it is possible to look up how all the respondents answered any one particular question we asked. For example, you can find out how the conciliators assessed the situation and decided what was needed, how they built trust, how they ran meetings, how they dealt with power disparities, how they defined and maintained neutrality and confidentiality, and (among other topics) — how they measured “success.“ Phase 2 materials were also coded, but we don’t have those results integrated into the sorted answers yet. That is coming.

How Did the CRS Conciliators Measure Success?

One of our round one respondents, Martin Walsh, said success could be measured on three levels. The first was if they succeeded in developing a plan of action and were able to carry that plan out successfully. For example, did they plan to hold negotiations between the aggrieved parties and the authorities to get the grievances out and responded to? If that happened — that was his first measure of “success.” The second level was what was the impact of the intervention? Did it lead to the result they were hoping for? And the third level was what changes have taken place, and what is going to be continued over time? Were their improvement in relationships? In institutions? “What is going to be the future of that community, that organization, or that institution?” His goal — which was echoed by many of the conciliators we talked to — was to solve the immediate crisis and do so in a way that long term changes were made, both to relationships, and often also to institutions. And very often (though not always) they were able to meet all three goals.

Most other respondents said something similar. They aimed to solve the immediate problem, but also to change relationships and structures so as to avoid future problems.

Stephen Thom, on the other hand, emphasized reputation: he saw referrals as a measure of success. (Thom’s answer is on the same page as Walsh’s—just scroll down a bit.) He reported that he would often get called by a stranger, saying someone else suggested that they call, because CRS had helped them in the past, so could they come help out the caller. “We must be doing something right,” he said, or “we wouldn’t be referred. “ He also said:

I get a great deal of satisfaction coming out of certain cases where you just know the parties are very cordial. I’ve had people say, “We want to take a picture, we want to document this agreement.” I’ve had people come to me and say, “This is the first time we’ve ever had anything written that we can hold onto that’s really spoken to this issue that has been going on for years.”

So Maybe They Didn’t Do the Impossible, But They Did the Very Hard. And Now They Are Gone. But We Aren’t!

So yes, we agree with Dick! CRS did resolve lots and lots of long-lasting, serious racial, religious, gender (etc.) disputes successfully, even though, overall, these kinds of conflicts still persist. We were not wrong to call them intractable.

Which is why it is such a loss to have CRS closed down. They are needed now, perhaps more than ever. And their loss is going to be felt deeply by the many people who have known and trusted them in the past, and those who need them, but never will get the chance to benefit from their efforts.

We hope that many people will check out some of these interviews to learn what they did and how they did it, so others can take over and fill the void that CRS’s closure has left. And if you can, please join us (Guy and Heidi), Grande Lum, and Bill Froehlich on December 3 at 10:30-12:00 Eastern when we talk about this work!

Another resource that is available for those who are interested is a book telling the history of CRS and recounting even more stories than the ones we have on our website. The first edition, written by former CRS Associate Director Bertram Levine came out in 2005. It was titled Resolving Racial Conflict: The Community Relations Service and Civil Rights, 1964-1989. Former CRS Director Grande Lum added a lot more material for a second edition, which is now entitled America’s Peacemakers: The Community Relations Service and Civil Rights). This edition was published in 2020. We recommend it highly!

Please Contribute Your Ideas To This Discussion!

In order to prevent bots, spammers, and other malicious content, we are asking contributors to send their contributions to us directly. If your idea is short, with simple formatting, you can put it directly in the contact box. However, the contact form does not allow attachments. So if you are contributing a longer article, with formatting beyond simple paragraphs, just send us a note using the contact box, and we'll respond via an email to which you can reply with your attachment. This is a bit of a hassle, we know, but it has kept our site (and our inbox) clean. And if you are wondering, we do publish essays that disagree with or are critical of us. We want a robust exchange of views.

About the MBI Newsletters

Two or three times a week, Guy and Heidi Burgess, the BI Directors, share some of our thoughts on political hyper-polarization and related topics. We also share essays from our colleagues and other contributors, and every week or so, we devote one newsletter to annotated links to outside readings that we found particularly useful relating to U.S. hyper-polarization, threats to peace (and actual violence) in other countries, and related topics of interest. Each Newsletter is posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please ....