Massively Parallel Problem Solving and Democracy Building: An Ongoing Response to the Threats to Democracy in the U.S. - Part 1

Newsletter 282 - October 3, 2024

APOLOGY AND CORRECTION!! We accidentally misspelled Caleb Christen's last name in our last newsletter. To make it up to him, we'll give an extra shout out to the work he and Vinay Orekondy (and others) are doing with Better Together America. If you haven't read that newsletter, or watched or read our conversation with Caleb and Vinay, we recommend it highly. It also provides a great lead in to this series of posts, as people and organizations engaged in the hubs Caleb and Vinay describe are also examples of people and organizations acting in some of the MPP roles we will be describing in the last installment of this 5-part newsletter series on massively parallel democracy building (MPDB). Indeed, the network that Better Together America is building is a great example of MPDB at work.

On September 16, 2024, the Toda Peace Institute published a paper that Guy and I wrote entitled "Massively Parallel Problem Solving and Democracy Building: An Ongoing Response to the Threats to Democracy in the U.S." They published this as one of their "Policy Briefs" in their Global Challenges to Democracy Program.

This paper presents an overview and synthesis of a number of different things that we have been working on over the last several years, and forms the structure on which we are building a Guide to Constructive Conflict and Democracy, which will amount to a significant re-ordering and re-purposing much of the material currently on Beyond Intractability. Since it is such a foundational piece, we wanted to share it on Substack. It is far too long for one newsletter, however, so we are breaking it down into five newsletters which we will be sharing at the rate of one a week over the next five weeks. We are now posting it in its entirety on BI as well.

This first installment of the paper provides an introduction to many of the core ideas we present in the rest of the paper. We introduce six essential dispute handling functions that all successful democracies must be able to perform. We then give a quick overview of the challenges democracies commonly face when trying to perform those challenges, and suggest that a process akin to Adam Smith's invisible hand allows for "massively parallel" democracy building and problem solving, the key to democratic resilience. We end this installment explaining that the paper focuses primarily on U.S. democracy, as that is where our expertise lies. Coming in the future installments are:

Part 2: A deeper look at the threats facing U.S. Democracy

Part 3: The first of three installments looking at the factors that give U.S. democracy resilience against these threats. That newsletter ends with a list of seven goals that massively parallel problem solving and democracy building need to meet to best meet these threats and emerge stronger and more equitable than it was before.

Part 4: This installment describes each of these goals in more detail, explaining what they are, and why they are needed.

Part 5: Here we briefly describe each of the 53 roles we have identified that are needed, and, for the most part, are already being filled to meet the goals listed in installment 4. And we note that when we say "filled," we do not mean "full." There is room for and need for everyone to get involved in this effort!

We want to thank Olivia Dreier for urging us to write the policy brief and being patient when it took us a very long time. And thanks to Olivia and Rosemary McBryde for your editing and posting on Toda. We also very much appreciate Toda's willingness to allow us to repost the paper in our Substack Newsletter and on BI. We also appreciate Toda's support of our work. We have learned a great deal from our participation in the Toda Global Challenges to Democracy Program and look forward to working with you more.

Added on November 1, 2024: Since all the installments have now been posted, here are links to the entire series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 (corrected version) | Part 5

Overview

Having spent the last 35 years trying to catalogue what the peace and conflict resolution fields collectively know about the hyper-polarized intractable conflicts that are tearing apart so many societies, we approach democracy’s ongoing struggles from a somewhat different perspective than many. As we see it, democracy is, at its core, a system for handling the vast stream of disputes that characterize all societies, in ways that the public believes will produce wise and equitable decisions. When democracies are able to successfully reconcile competing interests in ways that enjoy broad support (or, at least acquiescence), then citizens are willing to “trust the system” and forsake the use of extreme (and, potentially, violent) political tactics.

Successful democracies rely upon a vast and multi-faceted array of civic norms and institutions to perform six essential dispute handling functions:

Vision: Cultivation of a shared underlying vision for society that is capable of binding citizens (and non-citizen residents) together despite their many deep differences.

De-Escalation and De-Polarization: Limitation of destructive escalation and hyper-polarization dynamics that can make shared, democratic governance impossible.

Mutual Understanding: Promotion of mutual understanding through the effective use of a broad array of trustworthy and trusted communication mechanisms.

Reliable Assessments: Reliable, fact-based and technical assessment of the nature and causes of societal problems and the advantages and disadvantages of alternative options for addressing those problems.

Collaborative Problem Solving: Utilization of collaborative problem-solving processes that are able to identify and take full advantage of mutually beneficial opportunities to generate pragmatic solutions to intractable problems.

Equitable Processes: Equitable decision-making processes and institutions that resolve disputes in cases where voluntary, collaborative processes are unable to make consensus or compromise decisions.

The Challenges Facing Democracy

From our perspective, the challenges facing contemporary democracies are due largely to their inability to adequately perform these vital functions at the full scale and complexity of modern society with its: vast array of competing interest groups; large numbers of unscrupulous, bad-faith actors; and large numbers of people with legitimate grievances – grievances which are extremely difficult to address in ways which leave everyone feeling fairly treated.

These problems have produced a kind of dysfunctional politics that is sharply limiting the ability of democratic societies to protect themselves from increasingly aggressive authoritarian geopolitical rivals. These problems are also leaving a great many citizens so disillusioned that they are seriously considering abandoning the principles of democratic pluralism and embracing an all-out struggle for political dominance that leaves little room for fellow citizens who hold differing beliefs. This is often accompanied by an increasing embrace of "strong" leaders who promise to do whatever it takes to prevail — leaders who often tend to have corrupt and authoritarian ambitions.

Failure to successfully address these multifaceted challenges really does constitute an existential threat to democratic societies. If these democracies fail and succumb to the principal alternative, a kind of 21st-century, high-tech authoritarianism, it may well be impossible for them to ever recover. That is why we argue that our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious threat facing humanity. It is destroying the democratic institutions that enable us to address all our other problems.

The Key To Democratic Resiliency: Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand

Despite all of these problems, democratic societies have, for centuries, proven themselves to be extraordinarily resilient and capable of surmounting many past difficulties and learning from (and correcting) their many shortcomings. This resilience is driven by the political equivalent of Adam Smith's invisible hand – the notion that all problems, including political problems, create opportunities for people who can figure out how to help solve them.

Unfortunately, this societal learning process is reactive – it lags behind the things that go wrong. The reason is that large numbers of people must first recognize the existence of a problem. They then must be willing to support people who are looking for and trying out ways to address the problem, rather than digging in and making the problem worse (as are people in the United States who use ultra-partisan approaches to problem solving which just deepen polarization and governmental dysfunction). It is this support for innovative solutions that gives people the incentive they need to work to solve each problem. While it would, of course, be preferable to anticipate and avoid problems in the first place, that is something that is even more difficult to do.

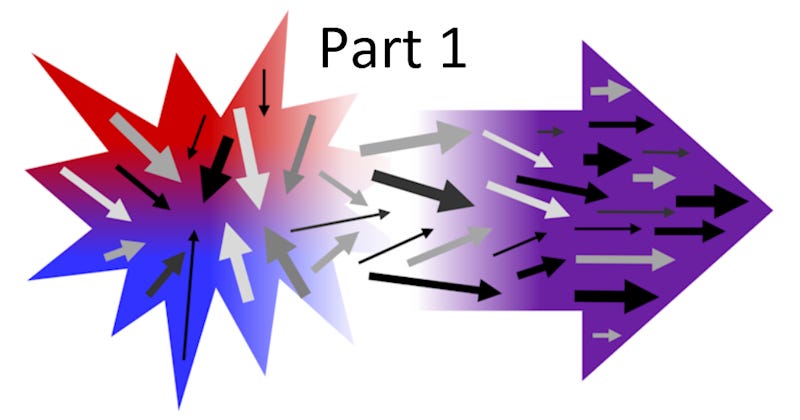

Massively Parallel Problem Solving

A great many people now recognize that the U.S. (and many other) democracies are struggling with crippling internal conflicts that are making problem solving all but impossible. While many fear democracy is doomed, and many others have just dropped out and put their “heads in the sand” (i.e. ignored the problems), others recognize that there are potential solutions available. A segment of these people has rolled up their sleeves, and gone to work, helping in myriad small ways to remedy one particular aspect of the problem, at least at one location. On Beyond Intractability, we have been assembling a preliminary inventory of these activities – efforts that often go unnoticed by academia and the mainstream media. We believe that if these efforts were more widely recognized, they would be able to attract additional support and participation by defusing the currently widespread sense of hopelessness.

The name that we give to this naturally occurring, societal learning process is “massively parallel problem solving” or “massively parallel peace” and “democracy building.” This approach relies on very large numbers of small, independent efforts, each trying to make a significant contribution to some specialized aspect of the larger problem. (The name came from the term “massively parallel computing,” in which many small computers work side-by-side to solve a problem that is far too complex for a single computer to solve on its own.) This approach contrasts sharply with all-too-common efforts to find some single grand solution or some political candidate that will somehow save us all. The problem is too complex for that. We really need a massively parallel, division of labor-based approach – one that that mobilizes our collective insights and energies to address first, our inability to work together, and second, the problems we need to work together to solve.

Right (And Left) Wing Populism: a Symptom Of the Problem, Not The Problem

Unlike many of our colleagues on the left, we do not see democracy’s ongoing difficulties as stemming primarily or solely from the rise of right-wing populist movements which are demanding radical change and supporting often unscrupulous leaders with aspirations for authoritarian power. Those leaders and their followers are, indeed, part of the problem. But they are not all of it. So, too, are the populists found on the progressive left – a group that, in its own way, has become so deeply disillusioned with “the system” that they, too, are demanding radical changes to traditional democratic institutions that they see as merely tools of oppression. Like the right, they are also committed to pursuing their demands, even if it requires finding ways to work around, alter, or eliminate these “oppressive” democratic institutions.

More importantly, both sides are completely certain that they are right, and that the other side is wrong, or even evil. So, both are completely unwilling to consider the interests or needs of the other side as legitimate, and they are unwilling to use traditional democratic problem-solving mechanisms to come up with collaborative or compromise solutions. They see politics and democracy as an all-or-nothing game, where winning is all important, no matter how it is done, no matter the costs – even if the cost is democracy itself.

While much of the strength of these movements (on both sides) is attributable to the clever tactics employed by often unscrupulous leaders and the media which exacerbates conflict for profit, much more of it is attributable to legitimate grievances and complaints about the many ways in which democracy’s elites have, in recent decades, left so many of their fellow citizens behind.

Solving these problems is going to require a multi-faceted array of efforts, each directed at a different aspect of the problem. This is something that we think is only possible with some sort of massively parallel approach – an approach that will enable us all to work together to craft a system that more wisely and equitably addresses the legitimate concerns raised on both the left and the right.

United States Focus

We are presenting this way of looking at the challenges facing democracy in the context of struggles in the United States. As a U.S.-focused project, we lack the expertise needed to determine the degree to which these ideas might be adapted to the challenges facing other democracies. So, we will leave that to others. We have long been uncomfortable with outside experts who try to push their ideas onto societies that they don’t really understand. That said, we do believe that this way of looking at democracy’s problems does offer useful insights that are likely to be quite broadly applicable.

In this report, we will start with a review of the multifaceted threat to US democracy – a threat that goes far beyond the 2024 election and Donald Trump’s candidacy. We then turn our attention to the primary and more hopeful theme of this paper, democratic resilience. Our goal is to highlight the highly decentralized, “massively parallel” process that has long enabled complex democracies to overcome serious difficulties in ways that yield a democracy that comes ever closer to living up to its ideals. We believe that the threats to democracy can most effectively be addressed first, by making existing solutions much more visible, so people develop some understanding and hope that change is possible. Then we need to help citizens understand the nature of these solutions and the ways in which they might contribute to their implementation. We then go on to describe six near-term goals for this massively parallel effort and the ways in which people in different roles can help the larger society to become a healthier, more equitable, and more resilient democracy.

Part 2 of this paper, explaining the threats to democracy that we are most concerned about, is available here.

Please Contribute Your Ideas To This Discussion!

In order to prevent bots, spammers, and other malicious content, we are asking contributors to send their contributions to us directly. If your idea is short, with simple formatting, you can put it directly in the contact box. However, the contact form does not allow attachments. So if you are contributing a longer article, with formatting beyond simple paragraphs, just send us a note using the contact box, and we'll respond via an email to which you can reply with your attachment. This is a bit of a hassle, we know, but it has kept our site (and our inbox) clean. And if you are wondering, we do publish essays that disagree with or are critical of us. We want a robust exchange of views.

About BI Newsletters

BI sends out newsletter 2-3 times a week. Two of these are substantive articles. Once a week or so we compile a list of the most interesting reading we have found related to our topics of interest: intractable conflict, hyper-polarization, and democracy, and we share them in a "Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links” newsletter. These links include articles sent by readers, information about our colleagues’ activities, and news and opinion pieces that we have found to be of particular interest. Each Newsletter will be posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please ….